In this article, we look at the art of judging boxing matches. The key topics are the four cornerstones of what judges should look for when scoring fights. The article also covers some of the pitfalls to avoid when scoring fights. (Spoiler alert: punch stats aren't as important as you might think they are.)

The article also introduces The Needle Method; a tried-and-tested method for keeping a running score count during the swings in any single round in order to avoid giving even rounds when every round should really have a winner. It is a must-read article for casual and serious boxing fans alike, particularly if you have ever had an opinion about a "robbery" in a boxing match without having a scorecard to support it.

If you want to score a fight, all you need is a pad and a pen or simply use the SharpBetting interactive boxing scorecard.

Judging the fights: how to score a boxing match

In professional boxing, matches are typically judged based on four key components:

- Effective Aggression: This refers to a boxer's ability to attack and land punches while maintaining control of the ring. Judges look for aggression that leads to scoring punches, rather than just reckless aggression.

- Ring Generalship: This assesses how well a boxer controls the pace and style of the fight. A boxer who dictates the action, positioning, and flow of the fight is usually awarded points for ring generalship.

- Defense: A boxer’s ability to avoid or minimize getting hit is a key factor. This includes blocking, slipping, ducking, and countering punches effectively to avoid taking damage.

- Clean and Effective Punching: This component focuses on the quality and impact of punches landed. Judges score based on clean, powerful punches that visibly affect the opponent, rather than light taps or glancing blows.

These components guide judges in scoring rounds to determine the winner of a boxing match. The final scorecard is a summation of the total points scored for each of the rounds in the contest. There are usually three judges for world title fights. Each round is three minutes long (two minutes in most women's matches) and there is a one-minute break between rounds.

The winner of a round is awarded 10 points for that round, the loser of the round is given 9 points. If a boxer is knocked down or touches the canvas with a glove, they lose a further point, resulting in a 10-8 score for that round. A second knock-down would make it a 10-7 round.

Further points can be deducted by the referee for infringements.

In rare cases, a boxer might dominate a round so significantly that a judge gives them a 10-8 round without scoring a knock-down but this is very rare. Similarly rare, it is possible for a boxer to dominate a round and win it by a score of 10-9 but if they then suffer a flash knock-down, the score for the round could be 10-10. They won the round, but lost a point for being knocked down. Both of these scenarios are very rare.

In title fights, there are three judges, each of them is located on a different one of the four sides of the ring. This ensures that each judge has a different view of the contest.

At the end of each round, the judges hand their individual scores for that round onto another official, and then they start the scoring of the next round. This means that they have no record of how they are scoring the bout as it progresses. They have no running total of their score, apart from they can recall in their head. This is why you will sometimes hear a judge say that they were surprised by their own scorecard.

Why do commentators make such bad judges?

(It's not their fault) - If you are familiar with the concepts of System 1 and System 2 Thinking, you will understand why boxing commentators and in-fight analysts often return curious scorecards and the whole boxing world cries robbery.

System 1 and 2 Thinking

- If you are doing a complicated task such as reverse parking your car, this requires System 2 Thinking. If your passenger was to ask you "what is 2 plus 2?" you would reply "4" without hesitation; it is possible to answer an intuitive System 1 question like that, while performing a complex System 2 action, the parking manoeuvre. However, if your passenger was to ask you "what is 37 x 3.5?", you would either have to ignore the question, or stop the car. You cannot perform two concurrent System 2 tasks.

And in boxing...

Commentating and judging both draw heavily on System 2 thinking. A skilled commentator isn’t simply reacting; they’re analysing patterns, anticipating sequences, managing timing, and selecting precise language in real time. That level of fluency might look effortless, yet it’s powered by a highly trained, deliberate System 2 process. They must recall background facts, integrate tactical understanding, interpret context, and construct coherent, engaging commentary while monitoring tone and pacing. It’s continuous, structured cognition under time pressure: System 2 operating at speed.

Judging also relies on System 2 but with a different, even greater focus. Instead of verbal analysis, it requires sustained silent concentration, accurate memory of exchanges, and consistent application of scoring criteria. Both roles are mentally demanding and rule-based, but the judge’s task is evaluative and cumulative, while the commentator’s is analytical and expressive. The two things cannot be done in parallel to any suitable level of quality.

Both of these cognitively demanding activities use System 2, and the two tasks are incompatible in real-time. Trying to maintain both tasks simultaneously (narrating for an audience while accurately scoring a fight) is like trying to sing and do mental arithmetic at the same time: possible, but neither is done well: both draw on deliberate cognition, but the attention required for one inevitably undermines the other.

Sure, you can try to do both, but one will always degrade. To judge well, you must observe silently and hold details in working memory. Speaking, as a commentator must, breaks that focus.

In practice, someone could describe what they’re seeing and think they are scoring, but that’s not judging. True scoring accuracy requires inner focus and a buffer against distraction, which is in fact the opposite of live commentary performance. Both roles demand deep expertise in reading a fight and they cannot be done in parallel.

And this is not just an opinion piece, it's science.

Average Confidence Rating (ACR)

Very few rounds in professional boxing are easy to score. As seen in the section above, it requires undiluted concentration throughout the duration of the contest.

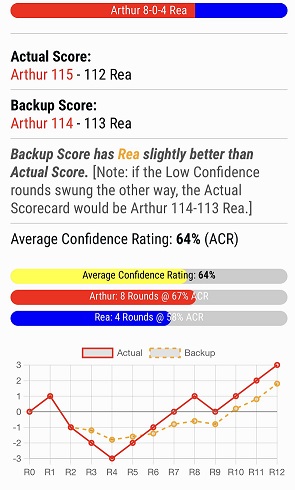

That is why The SharpBetting Boxing Scorecard requires the user to input their confidence rating (High, Medium, Low) for each round that they score. This approach reveals just how subjective the art of scoring really is. It also allows for a certain cooling off of the strong opinions about how individuals score the fights and feel so strongly about "robberies". Try it HERE.

Punch stats

Punch statistics, while interesting and sometimes indicative of the flow of the contest, are not considered when judging boxing matches. It is quite possible, and happens frequently, that one fighter lands more punches in a round than the other, but doesn't win the round. This is often seen as controversial but it isn't; it's a lazy way of shouting controversy when a fighter is not given a decision that most people feel is deserved.

One notable example involves Floyd Mayweather Jr., a master of defensive boxing. In some of his fights, Mayweather threw very few punches in certain rounds, yet still won them on the judges' scorecards due to his superior defense, counter-punching, and ring control. In his fight against Manny Pacquiao in 2015, for instance, Mayweather won some rounds while throwing fewer punches than Pacquiao because his punches were cleaner and more effective.

It is quite simple to understand why punch stats can be misleading. Assume you have a light puncher connecting with five messy, lightweight jabs in a round, while the opponent is landing fewer punches but with far greater impact, rocking the opponent each time. If the light puncher lands 5 shots but they are not thrown cleanly and effectively and the opponent lands one power punch that lands perfectly and wobbles the lighter puncher every time he is hit, and that pattern is repeated for the full three minutes of the round, then over the course of that round it would be very hard to award the round to the fighter with 5x the punch stats.

In order to illustrate this, let's do an extreme example. If Boxer A lands 100 punches in one round and nothing else for the entire 12-round fight and Boxer B lands 5 punches in every round, then the punch stats would be 100-60 in favour of Boxer A. "A" has outlanded "B" by a significant margin. But in this fictional contest, Boxer B would win the decision by a landslide score of 119-109... yes, it is an extreme way of illustrating a point, but it needs to be considered.

Ineffective aggression

Another area that is oftern misunderstood is whether a boxer's aggression is effective or not. Simply marching forward, throwing wild shots, not connecting cleanly, can often make it look like a fighter is "pressing the action" but if none of those shots are landing, the judge will not give that sequence of action any credit.

Often, when watching fights from the stands or from the sofa, it can appear that a fighter is pushing his or her opponent back, dominating with forward movement, but only if the aggression is effective is it rewarded. Sometimes the judges will have a vantage point that presents a far more accurate picture than the fan in the stands or sitting at home watching the fight.

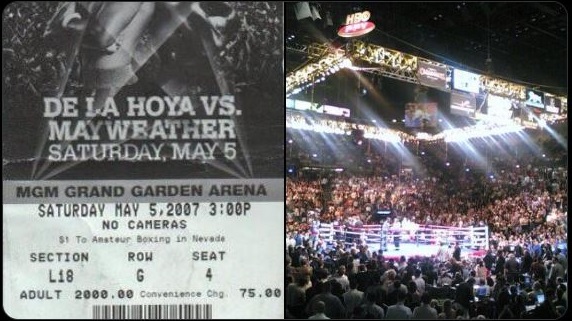

I was at the MGM Grand for Floyd Mayweather Jr's highly anticipated fight with Oscar De La Hoya in 2007. Along with the majority of the crowd in attendance, I thought Oscar had done enough to win. Some folk around me were screaming outright robbery. When I later re-watched the bout on a recording, I saw an entirely different contest.

Judging boxing matches cannot be done while multi-tasking

This brings me to another really important point. If you are judging a fight seriously, don't do anything else. You simply have to give it your undivided attention. When I have attended fights live, I have learnt that my feel for the score is going to be unreliable. If I am watching a fight in a bar, I won't even attempt to have an opinion on the score. If I have friends round to watch the fights with a few beers, I know any scorecard will be subject to distraction.

We have seen what happens when commentators nail their colours to the mast about their scorecards...

This is to emphasise that point; that anyone who is commentating on the radio or on the TV is doing one job; commentating. They are NOT judging the contest. They often give their opinion on how they are scoring the fight, but if they are concentrating on commentary they will not be concentrating on scoring, and at best, can only have a feel for the fight. No matter who is in the commentary box and no matter how respected they are, you must treat their scores with a pinch of salt. That includes Carl Frampton!

- From the Highfield Boxing podcast:

You can't really enjoy the fights if you are scoring them properly - it is mechanical

If you really want to have a valid opinion on a scorecard, which can be beneficial if you want to have a bet and exploit some value after the final bell and before the decision is announced, you really must not be distracted by anything.

Why does Social Media explode after "bad" decisions?

We put this question to LIVE & BREATH BOXING, a leading boxing betting expert on X:

Most fans judge through emotion. A lot of people score fights based on favourites — even when their guy is clearly losing, their brain still sees him ‘doing well’. Human psychology is wild, and that’s why the comment sections explode after decisions.

"Most fans judge through emotion. A lot of people score fights based on favourites — even when their guy is clearly losing, their brain still sees him ‘doing well’. Human psychology is wild, and that’s why the comment sections explode after decisions.

TV-viewers being persuaded about what they are seeing, AKA crowd-manipulation, is a powerful thing. And real-world factors can be influential: crowd noise, judge positioning, momentum, etc. — these are things that actually affect decisions in practice. They can be overlooked by a viewer sitting at home watching the fights. Sometimes volume and consistency does swing a tight round.

Online reactions aren’t organic anymore. Public perception can steer narratives, powered by a powerful big-fight promotion, and create ‘momentum’ around certain fighters. This is a reason why people online often sound so convinced even when the actual scoring criteria say otherwise.

Judging is still subjective. Even under the same rules, different judges value aggression, defense, or ring control differently. That’s why fans often get upset."

"Nicking" rounds

Many rounds of boxing at top-level are very closely contested. In such rounds, a savvy boxer will often step up the action in the closing seconds of the round to leave the judges impressed with the recent while overlooking the start of the round.

In these situations, the boxer is said to be "nicking the round" and it is a tactic used by a lot of the great fighters over the years. Bernard Hopkins was particularly good at executing the art of nicking rounds.

Sugar Ray Leonard, another Hall-Of-Famer, told his cornermen before his legendary fight with Marvin Hagler to alert him when there was 30 seconds left in each round. He was a master tactician, and if you watch this fight now even the untrained eye can see the difference in effort during the first 2:30 of a round, and the final half-minute.

There was a hugely controversial draw in 1999 when Lennox Lewis fought Evander Holyfield for the undisputed heavyweight title. Needless to say, most people didn't score the fight themselves and as such it certainly felt like Lennox has won clearly. But while he won the rounds he won clearly, that does not necessarily translate to winning the fight clearly. Playing Devil's advocate, let's say Lewis won five rounds by a country mile, battering Evander across all corners of the ring. Let's also say there were five rounds with very little action, but Evander did enough to nick all of them. Then add in two more rounds that were almost impossible to split and you have a perfect storm for a controversial draw. A fight that looks one-sided when viewed over 36 minutes of action, but was far from one-sided when scored on a round-by-round basis.

If you win the Olympics 100m final by 0.01s or 2.00 full seconds, you still only get one Gold Medal. The same is true in a round of boxing, if you win a round by a tiny margin or a landslide, it is still only one point difference.

Many respected boxing journalists and analysts will tell you that it was a close fight. In fact, at the time, Glyn Leach, the then editor of the UK's Boxing Monthly went with the headline "What controversy?" and was adamant in his editorial that Lennox was not the victim of the robbery that so many people thought they had witnessed.

Again, this was a fight in which the punch stats massively favoured Lennox Lewis, with the BBC drawing this conclusion:

Even the raw statistics of the fight strongly suggested the bout belonged to the British boxer. Lewis threw 348 punches that connected to Holyfield's 130, and he landed 137 jabs to the American's 52.

This is not to suggest that Lennox didn't deserve to have his hand raised; but I am suggesting that controversial results can often appear more controversial than they are in reality when the viewer doesn't know how to (or hasn't bothered to) score the match.

Watching the fight back 25 years later with the SharpBetting scorecard, we gave it to Lewis by four rounds: 116-112. Given some of the rounds were close, as Lennox was sometimes reluctant to stamp his authority, the back-up scorecard (based on confidence levels for the close rounds) has it a round closer: Lewis 115-113 Holyfield.

Treat each round like its own unique contest

Every round is a unique event. At the start of the round, forget everything that has gone on in earlier rounds. A classic mistake that fans make when judging boxing matches is awarding a round to a boxer for "doing better" than they did in the previous round.

Your scorecard will be the total of the 12 (or however many) rounds in the contest, with each round being a unique contest in itself. Each round should have no "memory" of previous rounds. A lot of novice judges fall into the habit of "sympathy judging"; awarding a round to a fighter who doesn't deserve to win but has done better than expected.

Just like how the official judges at ringside will hand in their scores to officials after each round, as recreational judges at home, we should also make sure we do not keep a running count of our scorecards. There is no upside to doing so, as it will only create biases. Instead, simply score each round on its own merit, and then tally up your scores for each round once the contest is over. Avoid all temptation to see how you've got it at the half-way stage. Again, this will only create bias and influence your score for subsequent rounds.

You can use the SharpBetting scorecard here [mobile, tablet, desktop] for fights of any duration.

Avoid even rounds

If you really cannot split a round, you should award both boxers a score of 10 points, 10-10. However, this is generally discouraged and even if it is by the most slender margin, it is usually possible to pick a winner in a round, and even rounds should be avoided.

Avoid sympathetic judging: just because you gave one boxer a very close round, that should not mean you have a slight bias towards the other boxer in the next round.

Again, avoid sympathetic judging, and just because you gave one boxer a very close round, that should not mean you have a slight bias towards the other boxer in the next round. This is another pitfall that novice judges will often fall into.

How to score a round

As the bell sounds to start a round, both fighters have perfect equitable parity. In other words, the round starts even. With every moment that passes, each boxer will attempt to impose their will on their opponent. As soon as the clock starts, as judges, we must now be totally focussed on what both combatants are doing, in every second of the round.

Look for who is in the centre of the ring, or using the perimeter of the ring to navigate the action on their terms. Which fighter is dictating the pace of the fight? Who is in control of proceedings? Who is initiating the action; which fighter is throwing the most effective counter-punches? Who is throwing the cleaner combinations at the right times in the action? The answers to these questions will help you decide who is winning the battle of Ring Generalship.

- November 2025: many observers felt that Zach Parker was unlucky not to get the nod against Joshua Buatsi in their fight. Buatsi made the valid point that Parker elected to take to the canvas EIGHT times during the ten rounds they fought. This fight had an Average Confidence Rating of less than 50% per round - this was an incredibly tight contest. If a judge sees one fighter consistently pulling himself off the canvas, that will not inspire huge credit under the criteria of Ring Generalship.

Don't just focus on who is throwing the most punches, or who is simply moving forward. The boxer's work needs to be educated. Aggression without composure should not be over-estimated, what we are looking for is Effective Aggression that has an effective impact on the opponent.

If the aggression is wreckless, it can actually be marked against the fighter, and instead, the opponent can be credited for Defence in response to the ineffective aggression. Keep an eye out for a boxer who is throwing a lot of punches but not hitting the target, as the opponent takes the shots on the arms and the gloves. Head-movement is also essential when assessing the defensive prowess of each fighter.

Punches must be Clean and Effective. This means the correct, knuckle part of the glove is making contact with the opponent. If the boxer is hitting cuffing shots, with the top or inside of the glove, these punches should not be rewarded. Glancing blows do not count as much as powerful punches. This again goes back to the punch stats conundrum. One power punch that rocks an opponent is a better way to win a round than ten glancing blows delivered in a slapping action.

All four of these components must be weighted evenly.

How to keep track of the action - The Needle Method

At the start of the round, make a mental picture of a dial with BOXER "A" on the left and BOXER "B" on the right. Your score needle is at the 10-10 position, dead-centre of the dial.

Ten seconds go by and neither fighter has done anything. Then BOXER "A" lands a jab. It is only a glancing blow, but it does land on the opponent. There wasn't much power on it, but it was a scoring punch so we move the dial in our head slightly to the left of centre. If NOTHING else happens in the remaining 2:50 of the round, we at least have a 10-9 winner of the round. That jab was enough.

Now, instead of that scenario, let's say that BOXER "B" then lands a combination - double-jab, right-hand, left-hook. It's a fast, powerful, eye-catching combination. Now the needle takes a bigger, significant movement, heading right on the dial.

We repeat this throughout the round, moving by small or large increments on the dial depending on the key elements that fit the definitions of the four scoring components. This methodology of scoring means that we don't need to remember what happened throughout the round. We don't have to watch a three-minute passage of action and then make a decision about who won the round based on everything that has gone on in that session.

Instead, The Needle Method allows us, as judges, to simply keep track on how far the needle has moved left or right on the dial. The round might be 2:00 old and the needle might be comfortably leaning in one direction. The other boxer might have some great success, but based on our yardstick for moving the needle on the dial, it might not be enough to move the round in their favour.

If you try this method for scoring fights, you will be surprised how easy it is to keep track of the action and how easy it is to avoid even rounds. And if you avoid some of the classic pitfalls in this article, while employing the needle methodology, you might have a lot more confidence in your scorecards than if you are simply scoring a round at the end of each session.

Body-shots

A lot of the ATG fighters are known for their body punching. In terms of how to judge the impact of a solid body-shot, this really comes under the topic of "what you like", as you will often hear. Boxing scoring is subjective.

Much like you may think that one solid uppercut is enough to swing a round in favour of a fighter who has just been hit by six successive jabs, the same approach has to be taken when weighing up the impact of attacks to the body.

Showboating

Showboating is entertaining for some but totally irrelevant for the scorecard. It can in fact be counter-proactive. Sometimes a fighter will act up, mean-mugging, or displaying some other performative action to suggest he has not been hurt when the opposite is often the case.

Pull-up the Joshua-Dubois fight from September 2024. Count the number of times AJ is rocked in the contest, and then count the number of times he sticks out his tongue, pounds his chest, and mocks Dubois. While being totally dominated for five rounds, there is only one reason why he is showboating. It is a desperate attempt to act like he hasn’t had the contest torn away from him, and to make it look like he still thinks he can win.

Ben Whittaker does a lot of showboating, and why not, he is incredibly good at it and he has gained a massive following because of it. But it divides fans, particularly the traditionalists who see it as disrespectful to the opponent and to the sport. For every minute he spends showboating with his Drunken Master antics, it’s more time he’s NOT winning points based on the four scoring criteria that the judges are looking for. In fact, in this clip, you can see the referee is visibly annoyed by the showboating, so the judges at ringside are unlikely to be looking at it favourably.

You could call it ring generalship at a stretch, but judges will rarely give credit to a fighter for turning a crip-walk into an Ali-shuffle while windmilling a right hand from out of range, no matter how impressive it is as an athletic endeavour.

Boxing off the back foot

Ring Generalship and Defence are two of the four main cornerstones of boxing. So it stands to reason that boxing off the back foot should be rewarded when assessing fights. Too often a boxer is described as “running” when he/she is in fact showing acute boxing awareness by using every inch of the ring to stay out of harm's way.

The problem with boxing on the back foot is that it’s not very fan-friendly. The desire for aggression, even if it’s wreckless and ineffective, offer trumps the quality boxing displayed by a more defensive fighter.

This is often the view of fans commenting on boxing matches and it has never been so prevalent as in the aftermath of the Beterbiev vs Bivol fight in October 2024.

The art of boxing is often described as hit and don’t get hit.

There is a strong case to be made that Bivol swept the first SIX rounds in that fight. Anyone with that scorecard would likely be ridiculed and dismissed but it is a valid point-of-view and one that recognises the art of defensive boxing. The art of boxing is often described as “hit, and don’t get hit”.

In the days following this quite superb fight, one commentator posted online that if the judges thought Bivol did not do enough to win the fight against Beterbiev, then those same judges would have put about six or seven losses on the resume of Floyd Mayweather Jnr.

It’s a good point.

In fact, the desire to discount defensive boxing while overrating ineffective aggression is not just a view among casual fans but it is also filtering into high-profile boxing influencers online and in podcasts.

In a post-fight podcast, Adam Catteral, a highly respected boxing analyst and one who is not shy about stating a controversial opinion, went through his scoring of the fight. He said about the defensive acumen of Bivol: “I'm not rewarding (it) because it's his job to defend himself in my eyes, the way I score a fight”.

Quite frankly, that is simply not how you score a fight. Boxing is indeed subjective, but that does not mean a judge can decide to ignore the defensive skills on display because they are only interested in offence. That is not how it works.

Anomalies

There is an urban myth that Willie Pep won a round in a boxing match without throwing a punch, because his defence was the superior component in that three-minute period.

However, no official record for the absolute lowest number of punches thrown to win a round in professional boxing, but there have been instances where fighters have won rounds by throwing very few punches. This usually happens when one boxer clearly dominates the ring with effective defense, ring generalship, or a strong punch that has a visible impact, even if they don’t throw many punches.

There is no precise number universally documented, but in rounds with minimal action, it's possible to win a round with just a handful of effective punches if the opponent is ineffective or inaccurate in their aggression.

It should also be noted that if the referee does not officially call a knockdown, even if it seems clear that one occurred, the judges are required to score the round as though the knockdown did not happen. The referee has the sole authority in the ring to decide whether a fighter was knocked down or slipped. Judges base their scoring on the referee's official rulings and actions, so if a knockdown isn't called, they cannot credit it as one.

This can sometimes lead to controversy, as the visual evidence might suggest a knockdown, but without the referee's official call, it doesn't count on the scorecards.

Another area where "visual evidence" can be misleading when drawing conclusions about the correct winner of a distance fight is when assessing which boxer is more marked up; which one has more facial damage and bruising. This is totally irrelevant and yet it is often cited as evidence for one boxer having the better of the other. Usyk had facial damage after beating Antony Joshua and Tyson Fury. Bivol had facial damage after fighting Beterbiev. So what?

When you accept that facial damage can be administered in just thirty seconds of action in a 36-minute fight, it is very hard to draw any valid conclusions based on which boxer is more marked up.

An 8-7 round?

In their fight in October 2025, Sebastian Juarez was dropped by Demarcus Layton in the opening seconds of round one. Juarez then went on to drop Layton three times to win the fight. During those first three minutes, Juarez also had 2 point deducted for holding. Let's assume that Layton was allowed to continue to see out the round. How would you score it? With one knock-down apiece cancelling each-other out and Juarez winning the round, we start at 10-9 to Juarez. With two more Layton knockdowns, it's 10-7 to Juarez. So that is the score for the round, minus the 2 point deductions we end up at 8-7. Bizarre.

Give it a go

Why not pull up your favourite controversial fight, watch it in full and try scoring it for yourself using the SharpBetting scorecard here. It works on all devices.

Boxing on X

Be sure to follow some of these insightful boxing betting accounts on X, all of whom have contributed to this article and are power-users of the SharpBetting Boxing Scorecard.

____________________

Interactive live boxing scorecard - click here.

See all of our big-time boxing analysis here.

The 9th Round: The Most Important Round In History? Click here.

Jake Paul vs Mike Tyson has been announced for 15 November 2024. Why so serious?

Usyk vs Fury 2 - The Rematch: click here.

Don't forget to join our 11,000 followers on X at @SharpBettingGB.